more theory than anyone should be legally allowed to possess

I. Dear Reader,

All the way back in Issue #69, I linked to a series of episodes from the Ken and Robin Talk About Stuff podcast about the “axes of game design”. I’ve been thinking about them again recently and thought it might be interesting to look at each one. I’ll be referring to the summary on the Pelgrane Press blog as I comment on them.

So the basic exercise is trying to figure out the standard axes or spectrums on which every game can fit. The idea is for these axes to be as descriptive and objective as possible. While there is always going to be debate around the classification of specific games, the idea is that in a perfect world with perfect communication, that debate would have a truly correct answer. We don’t live in a perfect world but I’m happy to discuss things like this forever.

So here we go:

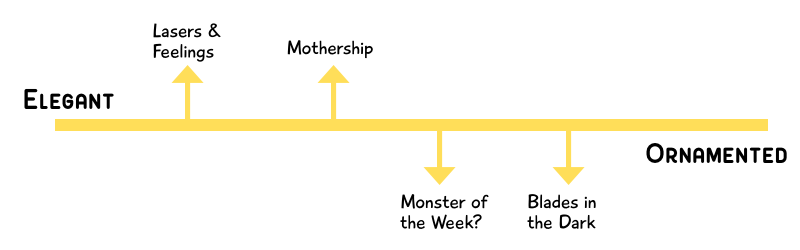

Elegance versus Ornamentation

A game has Elegance if all of its subsystems work in the same way, stemming from a central resolution mechanic, or is Ornamented if its many subsystems work in different ways

So the first axis is one of the strongest and makes a great example of the level of objectivity we can hope to achieve here. In some sense, the degree to which a game falls back on a single unified mechanic should be clear and measurable. At the same time, it’s not any indication of how “good” a game is. One-page games are highly elegant but they’re by no means “better” than longer games.

One thing that’s interesting is to see where PbtA falls on this spectrum. A game like Monster of the Week is pretty elegant because everything is essentially 2d6+stat. But does the number of moves, especially moves like Big Magic where you negotiate the effects of a spell or ritual, push it toward being more ornamentated?

Wide versus Focused

A game has Width if it supports play equally well over a long progression of power levels, or Focus if it works best at a narrower sweet spot.

I think this is where it’s probably best to start moving away from Hite and Laws’ wording. I think terms like “power level” is a wargame hangover. I think this is better phrased as “kinds of characters”. A game that is Wide is designed for a many kinds of characters. A game that is Focused is designed for specific characters or types of characters.

So you get something like Lady Blackbird (which has a cast of named characters on one side) as Focused and Risus (which is as generic as it gets in terms of character creation) as Wide. And yes, I put D&D 5e in there because I revel in the symphony of a hundred angry keyboards click-clacking away.

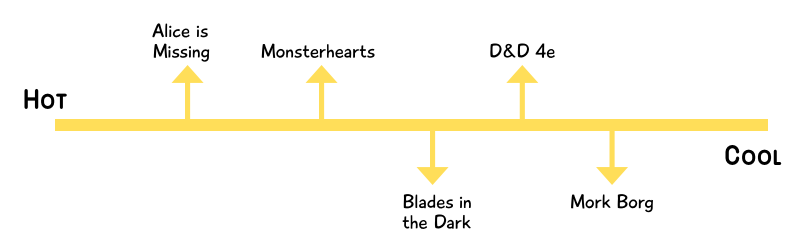

Directed Emotion versus Emergent Emotion

A game can have Directed Emotion, stemming from rules that lead you to feel a certain way, or Emergent Emotion, in which the reactions of players and GMs stem from the story content they introduce.

This phrasing is a little clunky because in their discussion, Hite and Laws felt that something like “Emotional versus Detached” was uncharitable. And I understand. But I also think that “Directed versus Emergent” is a bit like saying “Designed versus Undesigned”. I think the premise of the exercise that is “undesigned” isn’t a thing. If we want to describe a game as “neutral” on some axes, it should ideally fall somewhere in the middle. So I propose Hot versus Cool. Hot games try to stoke up emotions in the players. Cool games try to cultivate an air of cool, ironic detachment. They don’t want you to feel too strongly about the events of the game.

(The original article also mentions “Abstract rules for their mathematical or formal attributes, or Emotional rules when they grow out of the feelings they are meant to evoke at the table.” but this feels like it overlaps heavily with this point now.)

Applicability versus Versatility

A game has high Applicability if it is designed for a single highly specific player character core activity, or Versatility if it supports many possible core activities.

This is just Wide versus Focused for mechanics rather than characters. On one hand, they’re separate things. On the other hand, it’s clearly related. It’s a bit hard to imagine how a game might support wide characters with focused mechanics or focused characters but with wide mechanics, right?

Simulation versus Emulation

Games that focus on Simulation resolve events as they would unfold in a causal reality, or engage in Emulation, so that events unfold as they would in a movie or book, to keep the narrative running in a satisfying manner.

I’m not quite sure about this one. I’m struggling to understand which games commit to simulating real world physics. What’s the game on that end of the spectrum? I know OSR games revolve around the GM arbitrating physics impartially but in a game where dragons exist, how seriously do I take that claim? They would probably be in the middle of this axis at best if you ask me.

Ease versus Mastery

A game favors Ease when players can pick it up and run with it right away, or Mastery if it presents complex or elaborate rules or setting material, favoring those who take the time and brainspace to learn it.

For me, the important thing to ask ourselves here is whether the word “player” includes GMs. If it does, all rules-light games that might seen to favour Ease are not so easy anymore. (Which reminds me that I never actually talked about “affordances” as a design concept – an article for another day.) If we limit ourselves to “player facing mechanics”, then yes, I can see the spectrum. The problem is, of course, it looks exactly like my Elegant versus Ornamented spectrum.

What kind of games are Ornamented but don’t reward Mastery? What kind of games are Elegant but don’t favour Ease?

(The original article also uses the Harmonica vs Violin with Harmonicas being simple to play and Violins requiring more work. I think the overlap here is high.)

Canon versus Open

When it comes to setting, a game oriented around Canon presents a detailed setting with a set continuity meant to instill the same suspension of disbelief we apply to SF and fantasy worlds in traditional media. Open settings arise from the authorship of GM and/or players, with plenty of room to make stuff up as you go along.

This seems really clear. And I think examples might be unnecessary.

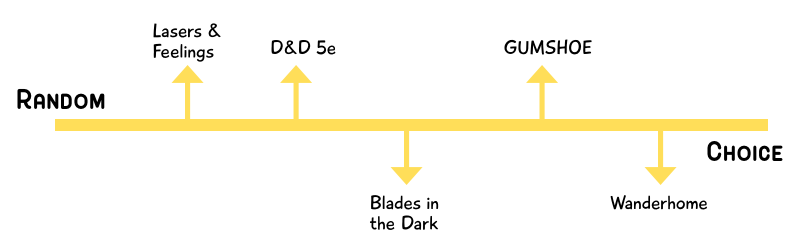

Randomness versus Choice

A game or system dependent on Randomness uses die results to work out what happens. A game that privileges Choice has players and GMs decide.

This also seems clear. Some games don’t give players the power to just choose what happens next. Some games push players to decide when they want spend resources to just make a specific thing happen.

This was a really interesting exercise for me. Lots of open questions that I’m excited to engage in nerdy conversations about. And just to be clear, Laws and Hite know what they’re doing. I have a great respect for their work. I just wanted a place to start building out on their ideas.

For further reading, check out this post about game design on two axes: player-driven versus GM-driven, prepped versus improvised.

Yours on multiple axes,

Thomas

We hit 3000 subscribers and I forgot to celebrate so I’m taking the chance now. Thanks for reading, folks! I appreciate having an audience – it’s a gift and I’m grateful for it.

Also, next week, I’ll do the monthly roundup of games on Itch. If you’ve released a new game on itch.io this month, let me know through this form so I can potentially include it.

And as always, if you can support the Indie RPG Newsletter patreon. That would be grand!

II. Media of the Week

Vampire cowboys!

III. Links of the Week

On Gizmodo, 30 games for heists, burglaries and bank jobs

On the Indie Game Reading Club, a written example for how conversations should work in Forged in the Dark games.

Judd Karlman outlines a campaign for idea for a group of mercenaries hired to defend a city.

Prompted by Here We Used To Fly, a nice exploration of “pure storygames”.

The new Soloist newsletter has an intro to solo games as their first post and it includes some suggestions from me.

If you’ve played Bite Marks, inventing werewolf slang is such a fun way to start. And on the ars ludi blog, there’s some nice advice on inventing new words.

The Global South Shoutout is a cool newsletter that shares designers from the Global South. This edition is about Forgotten Ballad, an OSR/NSR game by Brazilian designer Fellipe da Silva.

Some really interesting advice on running Call of Cthulhu 7e: “During the Bout of Madness, you should never, ever, ever, ever write anything internal to the psychology of the character. You should always, always always, write something external to the character.”

Paul Czege does an AMA on reddit talking about his new zine as well as games like My Life With Master and The Clay That Woke.

On Age of Ravens, a new mystery for Apocalypse Keys: people in Barcelona are getting stolen away to magical realms!

Zine Month

Dicebreaker has 31 games for you

Cannibal Halfling has two lists: ZineMonth roundup and Crowdfunding Carnival

Also, I’m a stretch goal writer on Chiron’s Doom, a scifi game of journeying to a mysterious monument. It’s designed by Nick Bate who made the wonderful Stealing the Throne!

IV. Small Ads

All links in the newsletter are completely based on my own interest. But to help support my work, this section contains sponsored links and advertisements. If you’d like your products to appear here, read the submission form.

Beneath Hallowed Halls is a Powered by the Apocalypse/Dark Academia TTRPG of friendships that run deep and bodies that are buried even deeper for #ZineQuest23.

These Stars Will Guide You Home is an Odyssey-inspired solo journaling rpg about an epic voyage looking for home in a mysterious archipelago.

Strikes & Spares is a slice-of-life tabletop roleplaying game with a slightly hard-luck/offbeat tone that’s set in a small-town bowling league. You can find the Kickstarter here!

The Connection Machine is a science fiction RPG about attachment, trauma and the search for meaningful connection. Explore a dream-like world to create stories about hope, grief, shame, freedom, attachment and love.

This newsletter is currently sponsored by the Bundle of Holding.

The One Ring 2e Starter bundle has the starter set, solo rules, and GM screen in one bundle.

There’s also a bundle of Godbound with the core rules and a handful of supplements for the OSR-adjacent game of demigods.

Hello, dear readers. This newsletter is written by me, Thomas Manuel. If you’d like to support this newsletter, share it with a friend or buy one of my games from my itch store. If you’d like to say something to me, you can reply to this email or click below!

Leave a reply to Chris Sellers Cancel reply